The Limits of Naturalistic Ethics

A Critique of Objective Normativity Without God

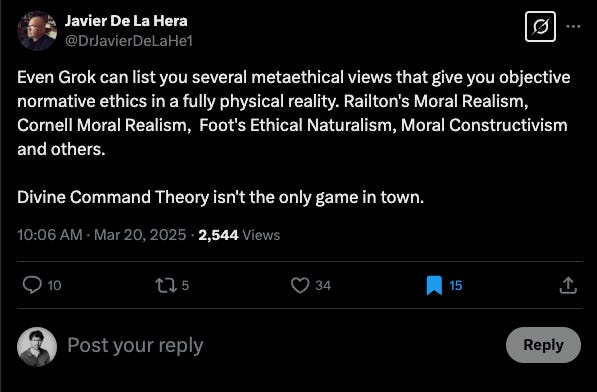

Yesterday, while scrolling through Twitter, I stumbled across a tweet from Javier De La Hera, an atheist and self-described nonbeliever. He claimed that there are several compelling philosophical frameworks capable of delivering "objective normative ethics in a fully physical reality." This piqued my interest, especially since I used to wrestle with these ideas back when I was a hardcore atheist myself. He mentioned Cornell Moral Realism and Railton’s Moral Realism—both of which attempt to ground morality in the natural world without invoking anything supernatural.

Cornell and Railton: Grounding Morality in Nature

According to Cornell Moral Realism, moral facts exist independently of human beliefs or attitudes. These facts are rooted in natural properties—like the observable features of actions or states of affairs—that we can discover through empirical investigation. Think of it like this: moral truths are out there in the world, waiting to be studied, much like the laws of physics. Cornell Moral Realism states these moral facts do not fully reduce to physical statements but “supervene” on moral facts.

When moral facts "supervene" on physical facts, it means that moral properties (like rightness or wrongness) depend on or are determined by physical properties (like actions or states of affairs). If two situations are identical in all physical respects, they must also be identical in their moral respects—moral differences can't exist without some underlying physical difference, even if they are not directly reducible to physical facts.

Then there’s Railton’s Moral Realism, which also sees moral facts as objective but ties them specifically to natural features that promote human well-being. Railton argues that we can understand what’s morally right through a scientific, naturalistic lens—by looking at what objectively supports human flourishing based on our needs and capacities.

Railton defines moral goodness in terms of what an idealized version of a person—fully informed and rational—would want for themselves or others. For example, he suggests that "an individual’s good" consists in what they would desire if they had complete knowledge of their circumstances and were reasoning instrumentally (i.e., choosing means to achieve their ends effectively.)

Both systems sound promising at first glance. They aim to give us a way to talk about "right" and "wrong" without appealing to gods, spirits, or mystical forces. But there’s a famous philosophical hurdle they need to clear: the is/ought problem, first articulated by David Hume. This problem says you can’t logically jump from a descriptive "is" statement (a fact about the world) to a prescriptive "ought" statement (what someone should do). For example, "This action causes pain" (an "is") doesn’t automatically tell us "You ought not to do it"—there’s a gap between facts and obligations.

How They Try to Bridge the Is/Ought Gap

Cornell Moral Realism tackles this by claiming that moral facts are natural facts, directly observable in the world. They’re not separate from reality—they’re baked into it. So, an "is" statement like "This action causes harm" carries an implied "ought"—"This action ought to be avoided"—because the property of "harm" itself has moral weight. No mysterious leap required; it’s all part of the same empirical package.

Railton’s approach bridges the gap differently. He ties "ought" to what objectively furthers human well-being, which we can study scientifically. If "This action promotes well-being" is a measurable fact about the world (an "is"), then it logically connects to "We ought to do this" because well-being is the naturalistic foundation of value. The "ought" flows from what we can observe about human needs and flourishing.

So far, so good. Both systems seem to dodge Hume’s challenge by rooting morality in the physical world. But here’s where naturalistic ethics completely hits a well..

The Psychopath Problem: Why Should Jones Care?

Both Cornell and Railton’s frameworks hinge on the idea that moral facts—like avoiding harm or promoting well-being—somehow apply to everyone. But what happens when someone just doesn’t care? Let’s imagine a psychopath named Jones. Jones was born with a brain condition that leaves him indifferent to the well-being of others. He can recognize factual statements like "This action causes harm" or "This promotes well-being," but he doesn’t give a damn. All he cares about is his own well-being and avoiding harm to himself.

Now, in what sense can we say Jones "ought" to avoid harming others or promote their well-being? Both systems claim their "oughts" are objective and logically derived from natural facts. But if Jones doesn’t care about those facts—say, the harm he causes or the well-being he could foster—where’s the normative "oomph"? Where’s the “binding force” of normativity? What makes him bound to act morally? Sure, we can say, "This action promotes well-being, so you ought to do it," but if Jones shrugs and says, "So what? I don’t care," the whole system seems to stall.

This is where naturalistic ethics starts to feel shaky. Cornell Realism says moral facts are out there, like gravity, but gravity pulls on everyone whether they like it or not—Jones can’t opt out of gravity. He is “bound” to follow the laws of gravity because we can theorize an actual naturalistic mechanism that explains why he is truly “bound.” Moral "bindingness," though? That seems optional for Jones. Railton ties morality to well-being, but if Jones doesn’t value anyone else’s well-being, why should he follow the "ought"? The logic holds only if he buys into the premise—and he doesn’t.

The Evolutionary Twist: Selfishness Might Win

It gets worse. Suppose Jones’s indifference isn’t a flaw but an advantage. Maybe his brain condition—his selfishness—helps him thrive in an evolutionary sense. He manipulates the "do-gooders" who care about well-being, exploits their kindness, and ends up with more resources, more mates, more offspring (whom he also doesn’t care about). This "minority strategy" could be a winning move in nature’s game. Evolutionary theory doesn’t rule it out—it’s agnostic about whether caring for others is "better" than not caring. Survival and reproduction don’t care about morality.

So, naturalistic ethics might give us "objective" rules—like "promote well-being"—but it can’t explain why Jones is mechanistically bound to follow them. His brain wiring says he doesn’t care, and evolution might even reward him for it. Where’s the natural force that compels him to align with these moral facts? "Binding" starts to sound like a metaphor with no teeth.

Naturalism’s Missing Rulebook

Back when I was an atheist, this was my sticking point and why I was a moral error theorist who thought all talk about naturalistic “objective moral facts” was metaphysical nonsense. Naturalists talk about "objective moral facts," but they never explain how those facts actually bind anyone. In a universe of atoms, quarks, and the void, where’s the intrinsic value? If all we are is biological machines—finite organisms with no cosmic purpose—then caring about well-being is just one preference among many. Some organisms care, like the do-gooders. Others don’t, like Jones. But where in this physical reality do we find a rulebook that says Jones is "wrong" to not care?

There’s no grand scorekeeper in naturalism. Jones could live his whole life selfishly, die happy, and face no consequences. The universe doesn’t care. We might say he "ought" to promote well-being, but that "ought" only kicks in if he already cares—and he doesn’t. Without a mechanism to enforce normativity, it’s all just competing preferences: Team Well-Being vs. Team Jones. Who’s "right"? Right according to what? Atoms and quarks don’t come with a manual.

The Theistic Answer: God as the Binding Force

This is where theism steps in with an answer. For theists, Jones is "wrong" because God says so. God’s the author of the rulebook—His Eternal Law declares that caring for others is good. Normativity gets its "binding force" from a Divine Sovereign who’s perfectly Good and who provisions ultimate Justice. Jesus made it clear: obey the law of love, or face eternal consequences. That’s a pretty strong "ought"—one backed by divine authority and the promise (or threat) of Judgment Day. People always forget that Jesus’ primary message was “Repent, for the Kingdom of God is at hand.” This is why he emphasized people to “Go and sin no more” and spoke about the consequences of eternal damnation more than any other person in the Bible.

In this view, Jones ought to care about others because God does, and God’s Will isn’t optional. Free will lets Jones choose, but his choices have eternal stakes. Sin—acting against God’s law—carries consequences that outlast this physical world. Without a Divine Mind issuing justice, normativity feels hollow. With it, "binding" makes sense: Jones is accountable, whether he likes it or not.

Conclusion: Naturalism’s Fatal Flaw

Naturalistic metaethics can churn out "objective" rules, but it can’t explain why anyone’s truly bound to follow them. Jones exposes the flaw: if morality’s just natural facts, and he doesn’t care about those facts, then the "ought" has no grip on him. Theism, for all its assumptions, at least offers a framework where normativity has teeth—rooted in a transcendent source with the power to enforce it. Without that, we’re left with atoms, quarks, and a void that stays silent on who’s right or wrong. To me, that’s where naturalism falls apart.

Nice stuff, but some Cornell realists (e.g. Brink) reject internalism about motives so the amoralist challenge doesn’t really apply — they already reject the conceptual necessity between morality and motives.

Ray, here is my favorite lecture by Alasdair MacIntyre that you might enjoy as a starting point to him and his thought:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=XjYLM1lw47Q&pp=ygUYY2F0aG9saWMgaW5zdGVhZCBvZiB3aGF0